The Trump administration has formally asked the U.S. Supreme Court to lift a temporary block preventing the deportation of nearly 200 Venezuelan migrants detained in Texas, citing serious safety and security risks. These individuals are alleged to be members of Tren de Aragua, a transnational criminal organization originating from Venezuela that has expanded across Latin America and, reportedly, into the United States.

In a court filing on Monday, Solicitor General D. John Sauer argued that the detainees pose “especially dangerous” threats while in prolonged federal custody. Sauer emphasized that the government’s use of the Alien Enemies Act (AEA)—a wartime statute that allows expedited removal of foreign nationals deemed threats—is warranted due to the severity of the behavior exhibited by the group in detention.

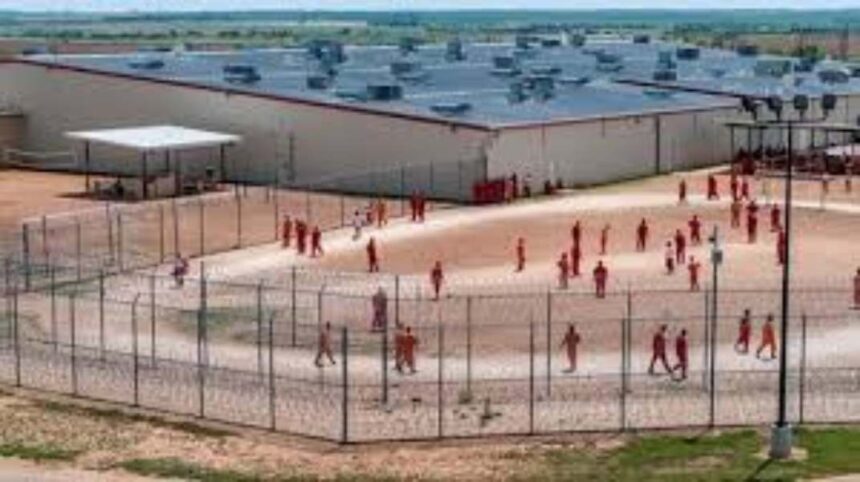

Supporting this claim, a sworn declaration from ICE official Joshua Johnson described a serious security breach involving 23 of the detainees at the Bluebonnet Detention Facility. The group reportedly barricaded themselves in a housing unit, threatened to take hostages, and defied direct orders. As a result, all individuals involved were transferred to the Prairieland Detention Center.

Johnson stated that “the organized and coordinated nature of the detainee misconduct threatened the security, safety, and order of the Bluebonnet facility,” prompting the emergency relocation. According to the government, such actions highlight the urgent need to proceed with deportations rather than continue indefinite detention.

Sauer’s filing also addressed the procedural aspect of the removals. He asserted that the migrants had received sufficient notification and time—three weeks—to file legal challenges through habeas corpus petitions. Yet, no filings have been submitted in the Northern District of Texas by any individuals facing removal under the AEA. This, the government claims, underscores the lack of merit or urgency in their legal defense.

The solicitor general is now asking the Supreme Court to modify its recent administrative injunction, suggesting it should only apply to deportations carried out under the AEA, while permitting removals under standard Title 8 immigration authority to move forward. The administration maintains that most of the individuals in question are still eligible for deportation outside the scope of the AEA.

The broader implications of the case involve the intersection of immigration law, public safety, and executive authority. The government’s strategy reflects an increasing willingness to use emergency powers to bypass longer administrative immigration proceedings, especially when detainees are believed to pose national security risks.

Tren de Aragua, the gang at the center of the controversy, has drawn international attention for its involvement in violent crime, drug trafficking, extortion, and human smuggling. U.S. officials assert that even within detention facilities, individuals linked to the gang have demonstrated highly organized and dangerous behavior.

The Supreme Court has not yet indicated whether it will lift the injunction or schedule a hearing. A decision is expected in the coming weeks and could shape the legal boundaries of detention and deportation authority for future administrations.

In the meantime, federal immigration enforcement is operating under heightened tension, balancing legal constraints with the pressing concern of managing detainees alleged to be affiliated with one of Latin America’s most dangerous criminal networks.