Is the US Finally on Track to Build a High-Speed Rail Network?

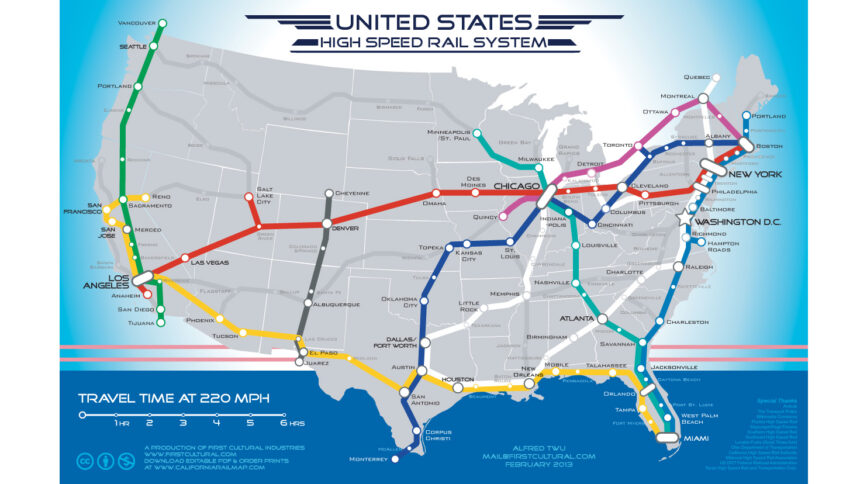

The United States, with a population exceeding 340 million, boasts a vast network of 71 interstate highways and more than 5,000 public airports. However, it remains notably absent of high-speed railways—a feature prevalent in countries like China, Japan, and various European nations. As America embarks on the construction of two high-speed rail (HSR) projects, along with additional future plans, there is growing curiosity: Is the US starting to catch up?

Rick Harnish, executive director of the High Speed Rail Alliance, expresses cautious optimism about the progress. “We now have two major projects under construction,” he mentions, explaining that the San Francisco to Los Angeles route faces significant geographical challenges due to California’s mountainous terrain. Conversely, the Las Vegas to Los Angeles line presents a much simpler construction scenario thanks to its flat landscape.

Additional projects on the horizon include a proposed HSR line linking Portland, Oregon, with Seattle, Washington, and extending to Vancouver, Canada, as well as another route between Dallas and Houston. Despite these ambitions, Harnish warns that progress on the Oregon-Washington line is slow. Moreover, uncertainties regarding the Texas corridor have intensified after the previous administration rescinded a federal grant of $63.9 million.

Global Comparisons

In stark contrast to the US efforts, China’s high-speed rail network is expanding rapidly, with expectations to surpass 50,000 kilometers (approximately 31,000 miles) by the end of this year. The European Union, too, boasts a substantial HSR network, measuring 8,556 kilometers, with Spain leading the way at 3,190 kilometers. The UK currently only has High Speed 1, a 68-mile link between the Channel Tunnel and London, while High Speed 2 construction is underway despite financial hurdles.

While definitions of high-speed rail may vary, the International Union of Railways suggests that trains need to achieve speeds surpassing 250 kilometers per hour (155 miles per hour). This raises the question of why the US is trailing behind both Europe and particularly China.

Will Doig, a rail industry journalist, describes America’s challenges: “We are a very car-dependent nation,” he states. “A significant portion of the population either feels no need for HSR or stands against its introduction in their communities.” He also mentions a lack of federal commitment to invest in rail infrastructure, complicating matters further.

Current Status of HSR in the US

Recently, the resignation of Amtrak’s head, Stephen Gardner, raised eyebrows, particularly as it followed pressure from the White House. Currently, Amtrak does not operate any high-speed trains. However, the company is set to implement 28 new 160 mph NextGen Acela trains along its Northeast Corridor, which connects Boston to Washington, D.C. Nonetheless, only about 50 miles of this 457-mile route permit speeds exceeding 150 mph. Notably, Amtrak is not directly involved with the aforementioned Californian and Nevada HSR initiatives.

The California High-Speed Rail project, projected for completion in 2033, and the privately funded Brightline West line from Los Angeles to Las Vegas, slated for 2028, symbolize the cautious steps towards a more interconnected rail system.

Economic Perspectives

Countries incorporating high-speed rail experience substantial economic benefits; for instance, Chinese cities report an average economic growth of 14.2% post-HSR construction. As China extends its influence through infrastructure initiatives in countries like Indonesia and Malaysia, some nations find themselves navigating complex financial dependencies.

Kaave Pour of 21st Europe highlights that Europe’s extensive HSR network reflects a historical commitment to public infrastructure investment. The think tank advocates for expanding HSR in the EU to connect major capitals and cities, emphasizing that if the US wishes to adopt HSR, a cultural shift toward public transportation is paramount.

In considering the future of HSR in America, Harnish argues that, “The federal government is crucial for success.” However, the recent withdrawal of federal support for the Dallas to Houston high-speed line casts a shadow over these ambitions.

| Country/Region | HSR Network Length (km) | Remarks |

|---|---|---|

| China | 50,000+ | Rapidly expanding |

| European Union | 8,556 | Well-developed network |

| United States | 0 | Under construction |

Amidst discussions of potential partnerships, Doig notes that geopolitical tensions challenge any hope of collaboration with China on rail projects. Nevertheless, he argues that a relationship bereft of animosity could yield remarkable advancements for America’s rail infrastructure.